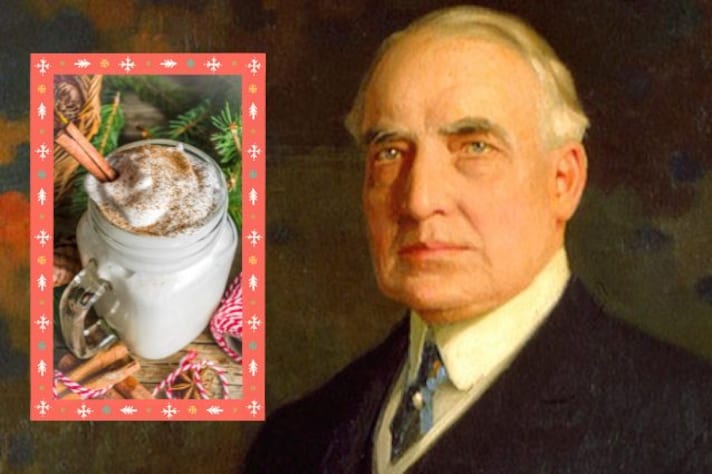

During Prohibition, America was officially dry—but the White House? Not so much. President Warren G. Harding, the 29th President of the United States, was famously fond of cocktails and reportedly kept the liquor flowing at private gatherings despite the nationwide ban on alcohol. At Christmastime, one drink in particular took center stage: the Tom and Jerry, a rich, frothy holiday cocktail so beloved it was said to be served in the White House even while the rest of the country was supposed to be sober.

What Exactly Is a Tom and Jerry?

If eggnog had a cozier, more theatrical cousin, it would be the Tom and Jerry. The drink starts with a sweet, spiced egg batter made from separated eggs, sugar, and warming spices like nutmeg and sometimes cloves or cinnamon. The whites are beaten into a fluffy meringue, the yolks are whipped with sugar and flavorings, and then the two are folded together into a thick, cloudlike batter.

When it’s time to serve, you spoon some of that batter into a warm mug, add a shot or two of brandy and/or rum, and top it off with hot milk or hot water. A quick stir and a sprinkle of nutmeg later, you’ve got a steaming, boozy, custardy drink that tastes like Christmas in a cup. It’s richer and frothier than eggnog, served hot instead of cold, and feels more like a ritual than just a cocktail.

From 1820s London to American Christmas Punch Bowl

The Tom and Jerry didn’t start in Washington—it started as a bit of clever marketing. In the early 1820s, British writer Pierce Egan published a popular book called Life in London, featuring two raucous characters named Tom and Jerry. To promote the book and its stage adaptation, he introduced a fortified riff on eggnog, adding brandy and rum and christening it the “Tom and Jerry.”

The drink crossed the Atlantic and caught on in the United States, where it gradually became a Christmas staple, especially in the Midwest and parts of the Upper Midwest and Plains. By the mid-1800s, bartender Jerry Thomas included it in his groundbreaking 1862 book How to Mix Drinks, solidifying its place in American cocktail history.

By the time Warren G. Harding entered the White House in 1921, Tom and Jerry was already a well-established winter tradition—one he reportedly had no intention of giving up.

The Harding White House: “Dry” in Law, Not in Practice

Prohibition technically banned the manufacture, sale, and transport of “intoxicating liquors” starting in 1920—but enforcement was famously uneven, and that included at the very top. Harding, known as a social, card-playing, whiskey-loving president, was said to host lively poker nights and holiday gatherings where the drinks flowed freely despite the Volstead Act.

Tom and Jerry reportedly became his Christmas drink of choice, served at seasonal White House parties as a warm, convivial way to toast the holidays. It was a drink with history, showmanship, and enough sweetness to feel festive—but enough alcohol to remind guests that, at least behind closed doors, Prohibition had its limits.

Why This Cocktail Refuses to Die

Tom and Jerry eventually fell out of fashion in much of the country after Prohibition, as tastes shifted toward simpler, leaner drinks and ready-to-pour holiday options. But in certain regions—especially Wisconsin, Minnesota, the Dakotas, and parts of Montana—it never really left. Pre-made Tom and Jerry batter still shows up in grocery stores there each December, and entire families have traditions built around making a batch, beating eggs by hand, and gathering around steaming mugs.

;Resize,width=767;)