When you think of absinthe, you probably think of the bohemian atmosphere of Paris during the Belle Époque, with bistros crowded with artists and cursed poets, bright colors on the walls and impressionist canvases. It's even more likely that it brings to mind the 90s or early 2000s, years in which absinthe was very popular among young people: a sort of "test of courage" to pass given the high alcohol content. But apart from French romanticism and the stupid youthful devastation we have done to our neurons, what is absinthe? Absinthe is an anise-flavored distillate, derived from herbs, flowers and leaves of the greater wormwood (Artemisia absinthium), from which it takes its name.

If we don't want to be so technical, however, we can say that absinthe is perhaps the distillate that more than any other carries with it an aura of magic, given by that famous green fairy that places the drink more in the world of the supernatural than in that of common mortals. An alcoholic beverage with an intense green color (often but not always), wrapped in an aura of mystery and prohibition. Once considered a cursed drink, capable of unleashing visions and madness, today absinthe has been reborn to a new life and fortunately more and more people are learning to drink it correctly (and responsibly). Let's see together everything there is to know about the most controversial alcoholic beverage in the world.

What is Absinthe and What is It Made From?

Absinthe is a high-alcohol distillate, traditionally produced from various herbs, among which Artemisia absinthium stands out, from which it takes its name. This plant, also known as greater wormwood, is characterized by a bitter taste and an intense aroma.

The production of absinthe involves several phases:

- Maceration: Herbs, including Artemisia absinthium, are left to infuse in alcohol.

- Distillation: the liquid obtained from maceration is distilled, concentrating the aromas and increasing the alcohol content.

- Coloring (optional): In some cases, absinthe is colored with the addition of other herbs.

The result is a complex and aromatic product, with a flavor that can vary depending on the herbs used in production. The entire modern process has made absinthe more "drinkable" because in the treatises on the preparation of the late nineteenth century that have come down to us we discover that the product was obtained only through distillation. In addition to the absinthe plant you can also find cinnamon, licorice, sage, hibiscus, lavender, other types of mugwort, lemon balm, mint, Pontic mugwort and hyssop. Usually the recipes include 6-12 ingredients but each distillery uses its own secret blend of herbs. The base of Artemisia absinthium, green anise seeds and fennel left to macerate is the only constant in all the distillates on the market.

The heart of absinthe is Artemisia absinthium, a plant with an intensely bitter taste. It grows wild in the Alpine areas and has a characteristic silvery green color. Since ancient times, its leaves and flowers have been used in herbal medicine for their tonic and digestive properties, but it was in the 18th century that this plant became the protagonist of a distillate destined to leave its mark.

The traditional preparation involves a distillation process that enhances its aromas and reduces its bitterness, but in the past some unscrupulous producers have added harmful substances to increase its visual effect and potential intoxication, contributing to its reputation as a dangerous alcoholic beverage. What has made absinthe particularly controversial is the presence of thujone, a natural compound contained in the plant, which is said to cause hallucinogenic effects, fueling the myth that the alcoholic beverage is capable of stimulating visions and altered states of consciousness. In reality, the concentrations of thujone in absinthe have always been too low to cause such effects, and its impact on health has often been exaggerated by disinformation campaigns orchestrated for economic and political reasons.

Today, absinthe is experiencing a new youth, and more and more people are approaching this fascinating and complex distillate. But how do you navigate the world of absinthe? How do you distinguish an authentic product from an imitation? And above all, how do you fully appreciate its aromatic nuances? Let's start with a premise: not all absinthe is green. In fact, in the past the color range of this liqueur was much wider, ranging from straw yellow to emerald green, with intermediate shades and even colorless versions (all distillates are transparent when freshly processed). The color, therefore, is not an absolute indicator of authenticity. However, it is true that today many absinthes on the market have a bright and artificial green, obtained with colorants. A real absinthe, on the other hand, has a more subtle and natural color, the result of the use of herbs and spices.

But color is just the tip of the iceberg. To recognize a real absinthe you have to go beyond appearance and focus on the substance. First of all, and it goes without saying, an authentic absinthe must be distilled. Distillation is a complex and delicate process that allows you to extract the aromas of herbs in a precise and controlled way. Be wary of absinthes obtained by maceration or with the addition of essential oils. Another fundamental element is the presence of green anise, a spice with an aromatic and dry flavor, a key ingredient of traditional absinthe.

The History, Origins and Controversial Fame

Absinthe, like many other alcoholic beverages, was born as a medicine and not as we know it. Since ancient times, our ancestors used artemisia in infusions and preparations to treat digestive and intestinal disorders. With the arrival of the Arabs in Europe and the advent of distillation, however, things changed and, in particular, between the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century we have the true birth of absinthe.

The inventor is said to be a French doctor fleeing the Revolution, Pierre Ordinaire, who was the first to come up with a recipe that combined mugwort with other aromatic herbs such as green anise, fennel and lemon balm. Also in this case the intention was to create a healing tonic but in a short time the drink became popular as an alcoholic beverage, conquering the salons of the French bourgeoisie and, subsequently, the artistic avant-garde. Ordinaire also thought of a catchy name: la Fée Verte (the Green Fairy), which has come down to us. In reality, as can also be read on the website of the Associazione Assenzio Italia, there is no certain information or precise temporal references on the origin of the product, even if it seems to have been actually invented between the end of the 1700s and the beginning of the 1800s by a doctor living in French Switzerland and thought of as a sort of remedy for every illness. A bit like Coca Cola invented by Dr. Pemberton.

During the Belle Époque, absinthe became the drink par excellence of Parisian cafés. The "heure verte", the green hour, marked the moment when poets, writers and painters gathered to sip this product with its intense and aromatic flavour. Great artists such as Edgar Degas, Vincent van Gogh, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Pablo Picasso celebrated it in their works, helping to make its connection with the world of art even stronger. Absinthe became a symbol of rebellion, creativity and intellectual freedom. Charles Baudelaire, Arthur Rimbaud and Oscar Wilde considered it a liquid muse, an elixir capable of expanding the mind and opening the doors of perception.

But it was precisely this excessive fame, combined with growing alarmism, that marked its downfall. From the early twentieth century onwards, absinthe began to be demonised. The main cause of this mistrust is the presence of thujone which is believed to have hallucinogenic effects similar to those of drugs. This news is true but as still happens today, journalists and doctors of the time forget to evaluate the quantity and the exposure time of the substance in our body. Thujone is hallucinogenic and is contained in absinthe but in such small doses that it has no psychotropic effects on people. However, the damage is done and the reputation of absinthe is compromised.

In reality, without wanting to sound too malicious, there were not only health reasons behind the prohibition started by France towards this specific alcoholic drink. Absinthe at the time conquered a huge market share, much higher than it has today, becoming more popular than wine and cognac. For the producers of these two drinks this was unacceptable and, having much more power than the young distillers, they contributed to fueling the defamatory campaign accusing absinthe of being the cause of widespread alcoholism and serious health problems. The turning point, in a negative way, came with the case of Jean Lanfray who in 1905 got drunk on various alcoholic drinks (including absinthe) and massacred his family without mercy.

The episode became incontrovertible evidence to demonstrate the dangers of alcohol with a continental resonance. In Switzerland, the homeland of the assassin, the prohibition of absinthe was even written into the constitution in 1907, France banned it in 1915, Italy banned it in 1939, and it was prohibited until the intervention of the Andreotti government in 1992. For much of the 20th century, absinthe was considered a forbidden drink, which added to the aura of mystery and legend that surrounded it. Consider that in Switzerland the ban on drinking absinthe was lifted only in 2005, 100 years after the assassination committed by Lanfray.

Italy was ahead of the game in Europe when it came to this kind of "liberalization." While absinthe was never outright banned in the Iberian Peninsula, its bad reputation made it practically impossible to sell. Italian law changed that, opening the eyes of other European countries. By the 1990s, absinthe was officially rehabilitated, thanks in part to scientific studies proving that the thujone levels in absinthe are harmless and don’t cause psychotropic effects. Italy's political move came after the European Union lifted its ban, provided the thujone content stayed under 35 mg per liter. But before our Legislative Decree on January 25, 1992, no one had dared to take action.

The real victory came in 2019, when the historic François Guy distillery in France earned Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status for Absinthe de Pontarlier. This certification guarantees the quality and authenticity of the product, protecting it from knockoffs and counterfeits. Today, absinthe is crafted using traditional recipes, carefully selected ingredients, and meticulous distillation methods that bring out its signature complex, aromatic flavor—a far cry from the myths that once surrounded it.

How is Absinthe Served and Why?

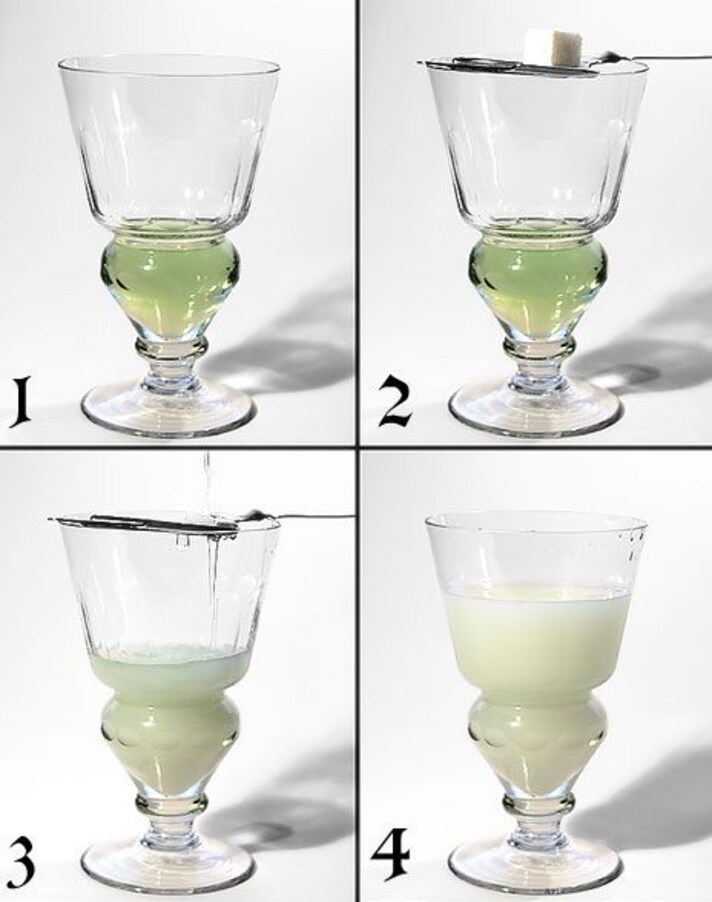

Forget modern flames and excesses. Absinthe was (and is) enjoyed with a slow and refined ritual, a true act of contemplation. You will need a few tools: a glass of absinthe, a sugar cube, a slotted spoon and cold water. Place the spoon on the rim of the glass, place the sugar cube on top and slowly pour in the cold water. Watch the magic happen: the absinthe becomes cloudy, transforming into a milky cloud, releasing inebriating aromas and scents. This phenomenon, called "louche", is the signature of authentic absinthe, proof that you are enjoying a quality spirit. The amount of water is subjective, but generally 3-5 parts water for one part absinthe is recommended. The important thing is to allow the "louche" to complete itself, to reveal all the botanical and sweet notes hidden in the liquor. Only then can you add more water, according to your personal taste.

The custom of setting absinthe on fire is instead a recent invention, born in the early 90s in some Eastern European bars, without any historical foundation and damaging to the flavor of the distillate. In reality, burning absinthe alters its flavor and destroys its delicate botanical aromas, nullifying the very essence of this drink. No historical evidence mentions fire as part of the original ritual: flambéed absinthe is only a recent invention, without ties to tradition.

If you want to live an authentic experience, forget the flames and follow the classic ritual, the one that has inspired generations of artists and intellectuals. We are already talking about a very difficult alcoholic drink. Oscar Wilde, an absinthe enthusiast, described its effects with words that amplify the myth: "After the first glass, you see things as you wish they were. After the second, you see them for what they are not. Finally, you see them for what they really are, and that is the most horrible thing in the world". The drinking ritual is iconic and contributes in some way to the beauty of the product, do not throw everything away.

;Resize,width=767;)